What Happens to the Arts When the Economy Suffers and What Can We Do About It?

Widespread unemployment. Shuttering cultural institutions. Struggling artists. Sound familiar? As events often repeat themselves, the difficulties of the current art world can be mirrored to the 1930s in the United States. The Great Depression, unsurprisingly, was a challenging period for artists and the arts. That is, until the New Deal’s Programs, including the Works Progress Administration, or WPA, and three other programs were created by the Federal government to support artists. It could be claimed, the federally funded projects changed the course of art history; the explosion and domination of American art and artists in the following decades can partly be traced back to these programs. In our present moment cultural institutions, from art museums to theaters, face new, unprecedented challenges and devastating financial setbacks. Perhaps we can take a page from the foresight of the New Deal Programs.

The year was 1933, President Roosevelt had launched the New Deal Programs to resuscitate the American economy, and a radical decision was made by his aide, a man named Harry Hopkins: artists were to be included as workers who could receive employment and financial assistance through the federal government. It is striking even to modern-day sensibilities the government was willing to view artists as equal contributors, like other workers, to the American economy, determining they too were eligible for stipends and employment schemes.

Through the four New Deal Programs which followed over the years, thousands of artists created countless pieces of artwork for government buildings, led art courses, and participated in art exhibitions from coast to coast.

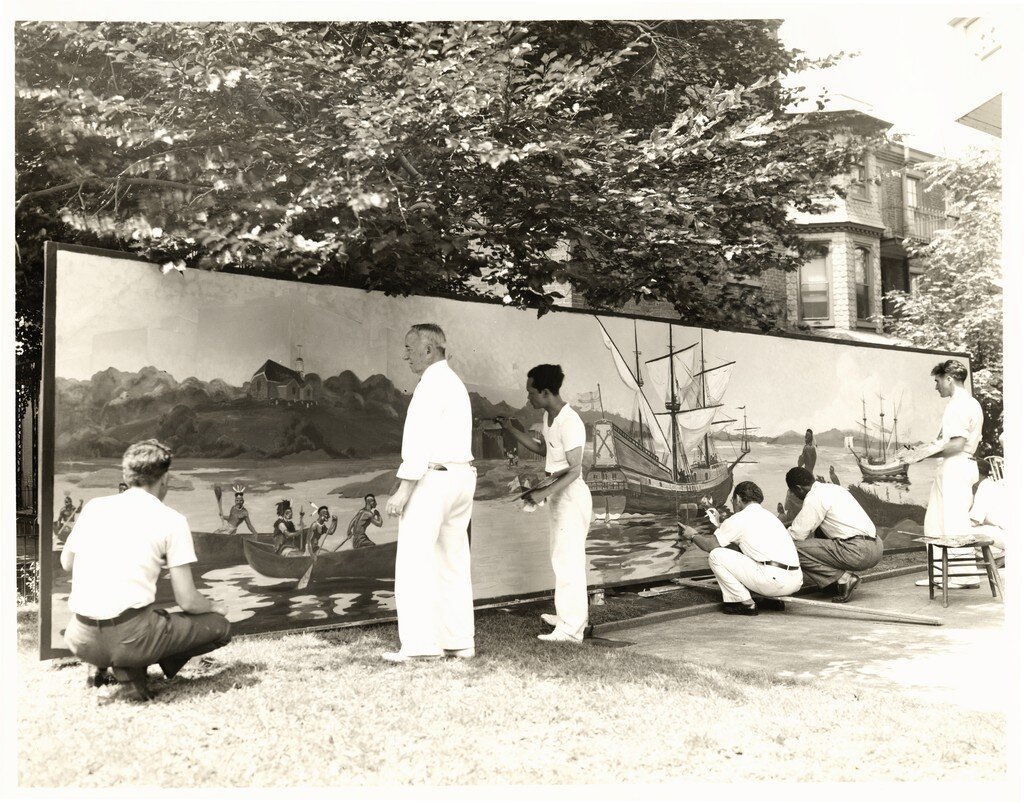

WPA artists painting a mural in Delaware. Photograph by Willard Stewart, taken during the 1930s. Image sourced from Artstor.

The Public Works of Art Project, or PWAP, started in 1933, was the first art focused New Deal Program launched. It placed artists on payroll and they benefited from weekly salaries. As Jerry Adler notes in the Smithsonian, nearly 4,000 artists were hired by the federal government to paint, craft, and sculpt pieces for government buildings. Those hired were expected to prove their skills, undergoing a test, and were sectioned off depending on their talent level, which correlated to the amount of salary for each artist. Two additional programs, The Section of Fine Arts which held competitions to commission artwork from artists, and the Treasury Relief Art Project, led by the Treasury department to employ artists to add pieces to federal buildings, were added. The last program launched in 1935, and most influential, was the Works Progress Administration, which in turn created the Federal Art Project.

The WPA, or FAP, was also the most expansive of the New Deal projects employing 5,300 artists, the largest number of artists of any program. Widely recognizable artists, such as Jackson Pollock, Dorothea Lange, Jacob Lawrence, and Mark Rothko, who each eventually shaped the direction of art through their careers, participated in the WPA in their early years.

Window display for an exhibition of WPA artists in Delaware. Photograph by Willard Stewart, taken during the 1930s. Artstor.

The Federal Art Project resulted in the creation of over 2,500 murals placed in schools, government buildings, hospitals, and other public spaces. It also had an educational component; art teachers were employed to run art classes for children and adults across the country. Community centers were also set up, acting as galleries and art classrooms in various states. Bringing art to previously ignored corners of America, out of the major cities, was an important aspect of the program. As Don Adams and Arlene Goldbard discuss in their paper New Deal Cultural Programs, while the program was led by the federal government there was an attempt, though not always successful, to vary the artwork and artists regionally. Artists were directed to create pieces relevant to the community they were working in and local artists were hired where possible.

WPA artist Richard Charles Zoellner’s (American, 1908-2003) “Life Along the Ohio River”. Library at the Greenhills Community Center, Greenhills, Ohio. 1938. Zoellner painted scenes depicting the commerce and industry on the Ohio River. Artstor.

Just the scale of the various art projects launched through the New Deal is astounding. Over the nine years they existed, from 1933 to 1942, over 10,000 artists were employed creating tens of thousands of pieces of art throughout America, in large metropolises and rural towns alike. One of the longest lasting, and greatest, impact of the federally funded projects was the establishment of a joint, American artistic movement.

As Alissa Wilkinson highlights in her article, a result of a national unification of the arts was a shared style of American art. Artists unionized themselves, forming the Artist’s Union. Adams and Goldbard point out that WPA artists were at last provided a living wage and through their contributions, felt they had a purpose to the greater good of society. Noted Abstract Expressionist painter, Willem de Kooning, drew his development as an artist to his experiences with the WPA, stating how he finally viewed himself as a professional artist. Part of the decision to include the arts in New Deal Programs can be traced to Roosevelt and his administration’s desire to inspire an art tradition specific to the United States, competing with other nations who were attempting to do so, such as Mexico and fascist-led Germany. Regardless of the political motivation, it was successful. In the following decades, American came to lead the art world, abounding in creative movements from Abstract Expressionism, to Minimalism, to Pop Art. Though the various federal projects ended with the start of World War II, the legacy of supporting artists, and bringing arts across the nation, continued.

Which brings us to present day. In a report published by the Brookings Institution in August, examining the impact of the current economic contraction on the arts sector, found around half of the 2.7 million jobs lost in creative industries, an estimated 1.4 million jobs, were in fine and performing arts. With no signs of the crisis relenting, what can we do to ensure the arts continue? Possibly a model inspired by, and drawn from, the New Deal could be the lifeline art industries need to survive. Viewing artists and the arts as essential contributors to the fabric of the American economy and society, as the federal government did in the 1930s, thus making them worth saving, is a vital first step.

Photograph taken by lauded WPA photographer Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965), “Family one month from South Dakota now on the road in California, vicinity of Tulelake, California”. 1939. Artstor.

https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/newdeal/fap.html

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/f/federal-art-project

https://www.gsa.gov/real-estate/design-construction/art-in-architecture-fine-arts/fine-arts/new-deal-artwork-gsas-inventory-project

https://www.umsl.edu/mercantile/events-and-exhibitions/online-exhibits/missouri-splendor/WPA.pdf

Adams, Don and Goldbard, Arlene. “New Deal Cultural Programs: Experiments in Cultural Democracy”. In Webster’s World of Cultural Democracy. 1986, revised 1995. http://www.wwcd.org/policy/US/newdeal.html#INTRO

Adler, Jerry. “1934: Art of the New Deal”. In Smithsonian Magazine. June, 2009. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/1934-the-art-of-the-new-deal-132242698/

Florida, Richard and Seman, Michael. “Lost art: Measuring Covid-19's Devastating Impact on America’s Creative Economy”. In Brookings. August 11, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/lost-art-measuring-covid-19s-devastating-impact-on-americas-creative-economy/?_ga=2.46419815.1320781201.1599858803-1998101497.1599858803

Wilkinson, Allisa. “Artists Helped Lift America Out of the Great Depression. Could that happen again?”. In Vox. June 22, 2020. https://www.vox.com/culture/21294431/new-deal-wpa-federal-art-project-coronavirus