The Rise and Fall of Connoisseurship

Just last month, a French auction house fired an employee who incorrectly priced a Qianlong vase at just $1,900, an estimate that couldn’t have made sense to its $7.5 million hammer price. Although the employee was what most would consider a connoisseur, the specialist mistakenly believed the vase was a copy. Herein lies the problem that often arises with the practice of connoisseurship: human error. The instinct that informs connoisseurs’ opinions is fallible, and methodologies in authentication have taken this into account over the years despite the seemingly precise nature of the practice. There are still cases where to be accepted into an artist’s catalogue raisonné or sold with a reputable auction house, the work must be presented to an expert to confirm the decision. Yet realistically, even an expert can be fooled and have their opinions disproven.

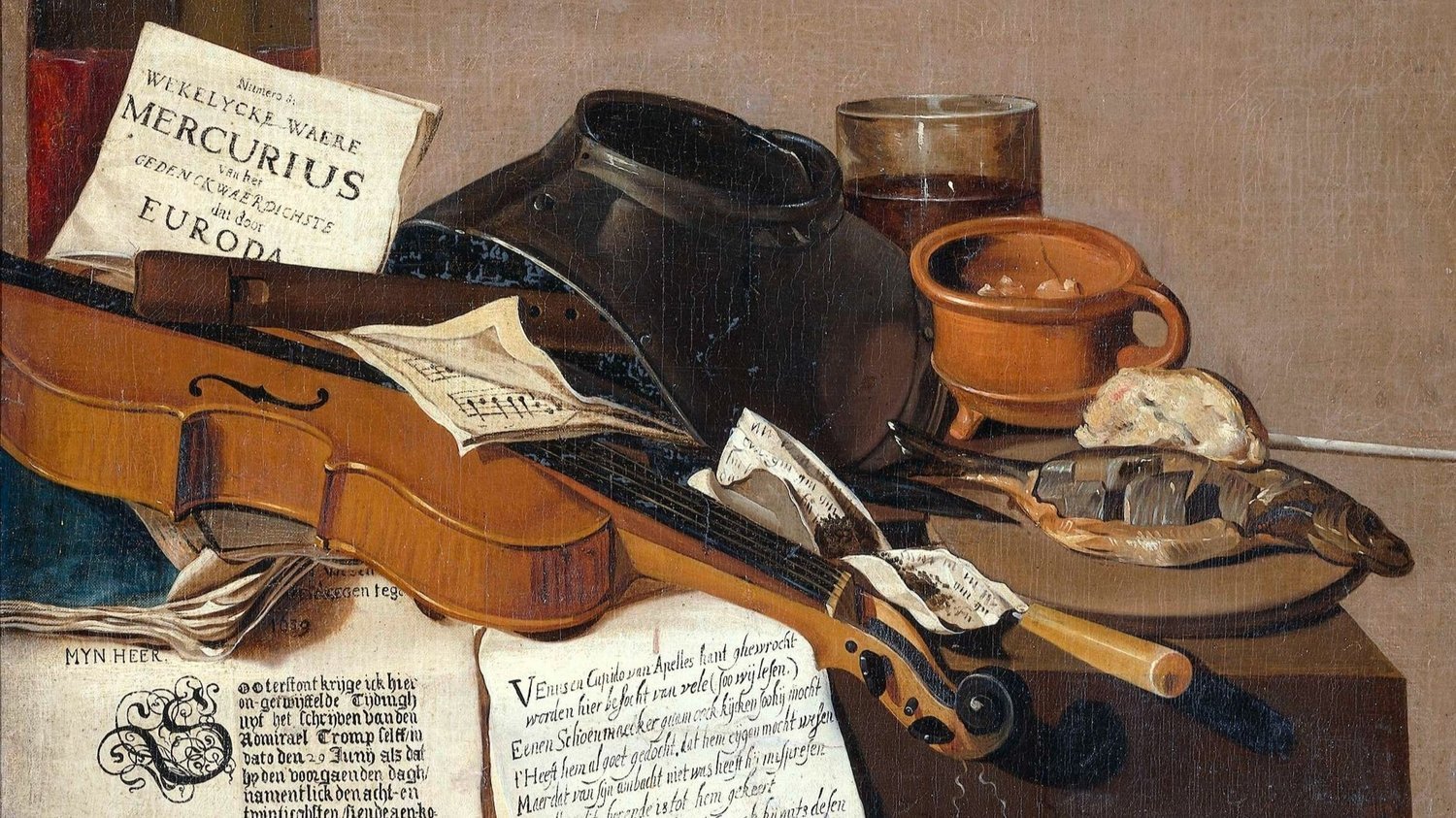

The notion of a connoisseur having “discriminating taste” is perhaps the most concise way to identify why the practice provides necessary expertise, yet creates suspicion in its blind faith approach. As Scott Reyburn asserted in 2021 in The Art Newspaper, “The definition smacks of male-dominated class privilege, an outmoded relic of Georgian England.” Reyburn explains that having artistic knowledge in the past was a privilege only afforded to a small group of wealthy white men, left unchecked by any other power. What was once a necessary professional deduction has come to be known as an elitist mystification. The unstable nature of the practice is a direct result of its origins, the “Morellian Method,” as well as the fact that the practice began as an exclusive access to knowledge. In the late 19th Century, physician and collector Giovanni Morelli established his own method for determining attributions of popular Italian artists. Morelli looked to hands, ear, and other parts of the body as tools for classifying a style of a particular artist. Although the method combats the weaker points of connoisseurship through formal analysis and scientific observation, he is guided by a ‘gut feeling’ as well. In the past, popular figures like Bernard Berenson and Thomas Hoving made entire careers out of the inexplicably strange feeling in their stomach, or a recognition that causes them to fall in love with an artwork.

Although their experiences may seem compelling, they are not based on empirical evidence. Connoisseurs are identified as those who are critically acquainted with a work of art, using a specific skill set and expertise that gives them the ability to identify an artist’s hand to the point of authentication. Yet the practice’s ability- and tendency- to overlook the possibility of human error contributes to waning support of the practice in isolation. This methodology doesn’t need to be eliminated, but it should be put into context, much like any other decision concerning authenticity or attribution.

The practice relies almost entirely on a level of subjectivity yet to be formally organized, and due to its proclaimed intuitive nature, likely cannot be. Instead of consulting other areas of research, the expert practice looks to an instinctual feeling that confirms an opinion. Practicing connoisseurship is just that, supplying an expert opinion. A New York Times article from this year notes the surprisingly fluid nature of opinions surrounding an artwork’s value. Stephanie Clegg paid $90,000 for a Chagall painting sold in 1994, and it was reappraised for $100,000 in 2008. When Sotheby’s encouraged her to sell the work, she was told she would have to send the work to France for authentication by a panel of Chagall experts, who determined the work was a fake. They now want to hold the painting and destroy it. But this is not an isolated incident of changing opinions, as the article also notes that in 1973, the Metropolitan Museum of Art reattributed nearly 300 paintings, and the curator of European paintings Everett Fahy upheld his belief that attributions are like any other field where knowledge is constantly evolving and results in changes.

With new approaches in collaborative research, scientific analysis, and developments in technology, informed and factual decisions push out the potentially dated elements of opinion. Researchers and scientists have access to methods that can date paint pigments, identify where artistic materials came from, and even look for additional layers of paint underneath the lasting image. Fifty years ago, it was impossible to email a specialist in another country high-resolution photos for a second opinion, and presently this is often an obvious step in confirming authenticity. In today’s art world, putting the evaluation in the hands of one person is simply unnecessary with the realm of resources provided by cultural institutions, museums, and galleries rather than a single actor. Terry Robinson, professor and author of the 2017 essay Eighteenth-Century Connoisseurship and the Female Body sums the issue up by noting “There will always be a case for analyzing and evaluating artworks with critical and intellectual rigor, but understanding what makes an artwork significant, compelling, or valuable should not ultimately be defined by just one person or one group.” Working as an appraiser is a profession that requires a level of humility to be aware of your own competencies and build your network with specialists from dealers, auction houses, conservation professionals, artists, scholars, and museums. An experienced professional knows that relying on a team of experts often yields the best results, as perhaps the practice of connoisseurship is not as useful in isolation as it was in the past.

from the desk of Madison Kelley

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Daab, John. Fine Art Connoisseurship and its Reckoning: Processes, Problems, and Appropriate Role for the Fine Art Connoisseur in the Authentication Process, 2007.

Morelli, Giovanni. Italian Painters: Critical Studies of their Works, Vol.1, London: J. Murray, (1892) pp. 64-82.

Reyburn, Scott. “Connoisseurship: Is It Time for a Comeback?” The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. The Art Newspaper - International art news and events, September 28, 2021. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/08/05/connoisseurship-is-it-time-for-a-comeback

Uglow, Luke. “Giovanni Morelli and his friend Giorgione: connoisseurship, science and irony.” Journal of Art Historiography, (2014) 1-30.