Art and Social Upheaval, Changes to the Design World After a Pandemic: an Opportunity for Creativity

What creativity comes out of a society wracked by disease, death, and suffering? Well, history may provide a clue. As scholars have noted, there are numerous parallels between modern-day experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic and the influenza pandemic of 1918.

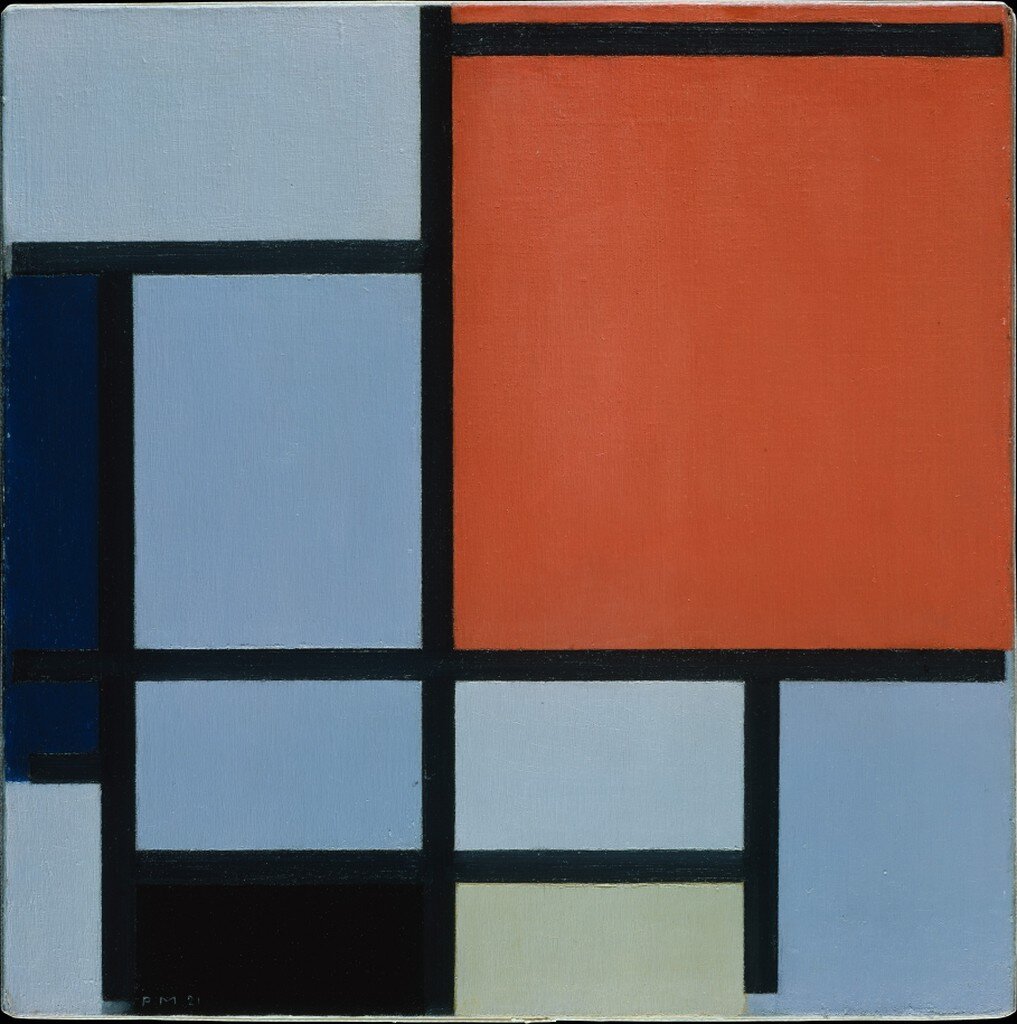

The art movements which dominated the 1920s show hauntings of this turbulent time in history. Artists begin to question preconceived notions on art and many are directly impacted by the 1918 flu or the death strewn battlefields tearing Europe apart in World War I. There is a shift toward the total abstract by De Stijl artists, a mockery of art by Dada readymades, and an eerie, unsettled nature to the Surrealism paintings. Seemingly too horrifying to depict any longer, artists move from the real world and turn toward a dreamlike, abstract world. Thus, if artists were impacted by the events of this period, how was the design world altered?

An example of artwork resulting from the De Stijl movement. Piet Mondrian’s (Dutch, Amersfoort 1872-1944 New York) “Composition”. Oil on Canvas. 19.5 x 19.5 in. 1921. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection. Image sourced from Artstor.

As Anna Purna Kambhampty mentions in her article “How Art Movements Tried to Make Sense of the World in the Wake of the 1918 Flu Pandemic”, one of the design movements which directly followed the 1918 flu pandemic was the Bauhaus. Begun in Germany in 1919 by Walter Gropius, the movement focused on multiple aspects of design and craftsmanship coming to emphasize mass production and utilitarian design.

Walter Gropius’ (American and German architect, teacher, and industrial designer, 1883-1969) Bauhaus school. Exterior view of workshop wing, view from south. 1925-1926. Weimer, Germany. Photograph taken on 05/15/2003 by Allan T. Kohl. Image sourced from Artstor.

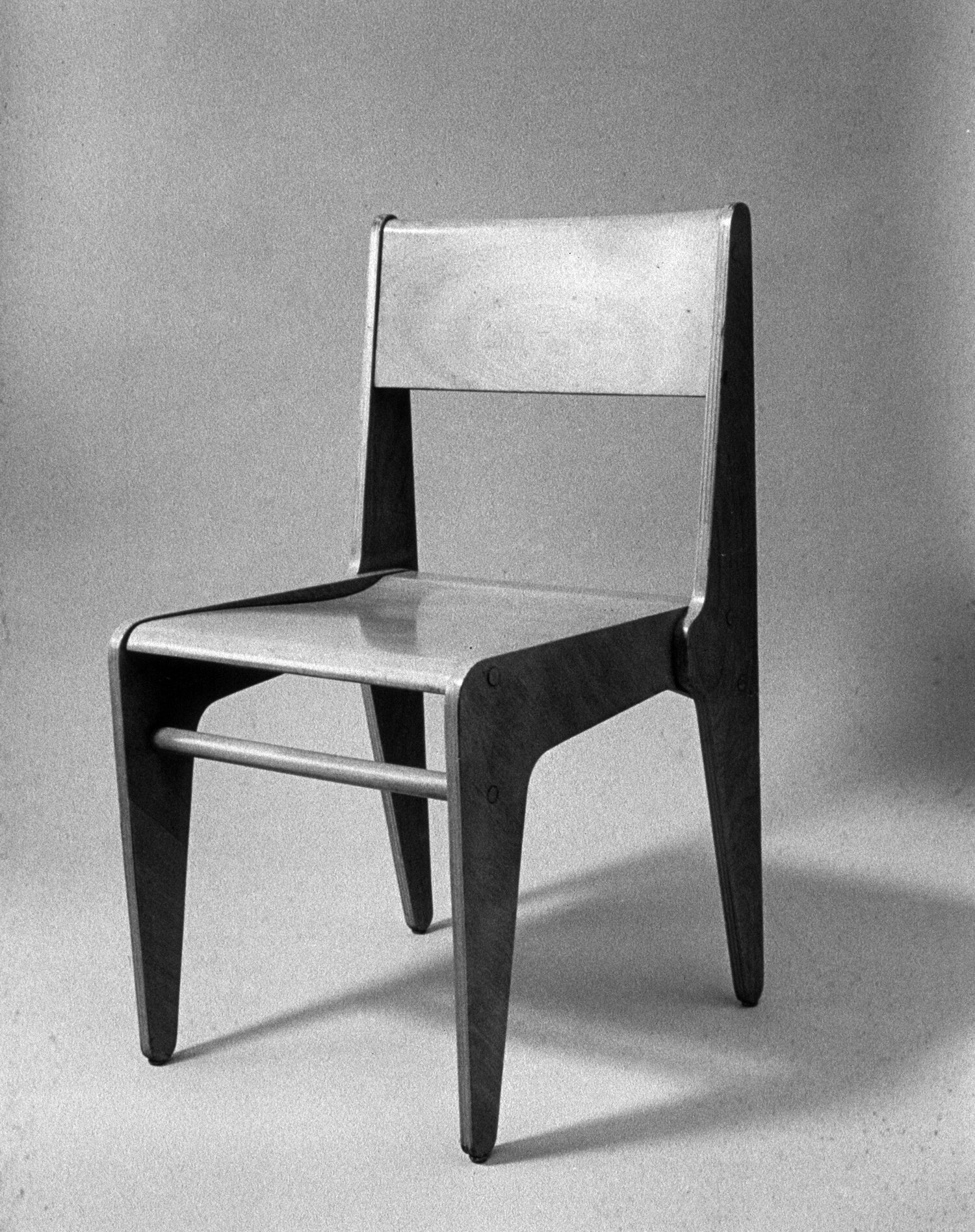

Kambhampty notes the simplified, industrialized furniture created by Bauhaus artisans and parallels it to the lingering fears of the flu pandemic. The metal furniture and leather straps allowed ease of cleaning and sanitation, as seen in Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s popular 1929 Barcelona chair or the chair designed by Gropius depicted below.

Walter Gropius’ dining room and chair. Gropius House. 1938. Lincoln, Massachusetts. Image sourced from Artstor.

Furthermore, the furniture and architectural designs fit well into the new utopian idealism of the Bauhaus. Much like artists casting off reality in favor of the obscure and dreamlike, Bauhaus created an idealized world for their designs. As Alexandra Griffith Winton notes in “The Bauhaus, 1919-1933”, Marcel Breuer, one of the Bauhaus instructors, believed eventually chairs would no longer be utilized, instead replaced with columns or even air. Hannes Mayer, who helmed the Bauhaus after Gropius stepped down, Winton adds, pushed the socialist ideas further and strove to highlight designs for the good of society, rather than for the individual.

Marcel Breuer’s (American and Hungarian architect and furniture designer, 1902-1981) dorm room chair. ca. 1937. Bryn Mawr College, Rhoads Hall. Image sourced from Artstor.

Thus, a child of a tormented world, the Bauhaus and its designers aimed for the creation of a world more perfect than what they experienced. One united by futuristic design and good craftsmanship.

This leads to the question, how is the modern-day design world going to respond to the COVID pandemic? What changes to interior design, furniture, or building spaces will be made? Much like the experiences humanity suffered through after 1918, leading to a desire to control their own environment through creativity, coming out of our present day moment we too are given the opportunity to imagine a new space.

Perhaps in large scale design projects new materials will be introduced and favored, or there will be a renewed emphasis on creating shared, but safe, public experiences and spaces after the world underwent isolating months apart. This is also the moment to make more immediate and intimate design choices in our own homes. As we turn to working from home, inhabiting our spaces far more than half a year ago, this is the time to rethink and be intentional about the pieces with which we choose to surround ourselves. Instead of a flimsy, cheap desk chair that was never really loved, take time to seek out and invest in an exciting chair, which is well crafted and inviting. That wall space with a forgettable poster could be re-imagined into a gallery wall, filled with artwork and images that inspire and comfort while supporting living artists which move you.

Only time will reveal the lasting impacts of the COVID pandemic, but history, and the Bauhaus, have provided insightful clues. Like them, may we too look to the future, hopeful we can craft a more perfect world, brimming with good design.

Selected Bibliography

Griffith Winton, Alexandria. “The Bauhaus, 1919-1933.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. August 2007, revised October 2016. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bauh/hd_bauh.htm

Purna Kambhampaty, Anna. “How Art Movements Tried to Make Sense of the World in the Wake of the 1918 Flu Pandemic.” In Time. May 5, 2020. https://time.com/5827561/1918-flu-art/